An endless number of films prominently involve characters dealing with their parents’ baggage. But only one film (that I’m aware of) saddles its characters with a dozen of their father’s antique monogrammed suitcases and then absurdly tasks them with lugging the baggage around an entire subcontinent. Some may think this is so on the nose that it reeks of desperation. But the literal baggage all over the screen in The Darjeeling Limited isn’t a placeholder waiting for a good metaphor that never manifested; it’s the whole point.

Two kinds of writers do what they’re not supposed to: those who aren’t good enough to get it right, and those who are so good that they can make their own rules. James Cameron deciding to call Avatar’s MacGuffin mineral “unobtanium” is the former, slathered in so much hubris that even spell-check was helpless against it. Not so for writer/director Wes Anderson. But to explain why the baggage non-metaphor works so well, we first have to backtrack a bit.

The Darjeeling Limited was Anderson’s fifth film, and—because he’s also made four films since—it currently sits at the exact midpoint of his filmography. That may look like a tidy chronological convenience for some of the points I’m about to make, but The Darjeeling Limited represents an actual crossroads for Anderson. It was a course correction against his previous film, it was the first hint of a changing set of visual interests and priorities, and it concluded the first thematic arc of his career.

“The titular train of the film is the most claustrophobic main location of any Anderson movie.”

Anderson’s previous film, 2004’s The Life Aquatic, is—to the eyes of this viewer—his least interesting film (and with a MetaCritic score of 62, it remains his worst reviewed). It was the first Anderson film where the script seemed to exist in service of the quirk rather than vice versa. Like the most insufferable hipsters, the degree to which it was into itself was immediately apparent. There is so much palpable effort in the production design of The Life Aquatic that it swallows up the screen.

Comparatively, The Darjeeling Limited had the least obvious production design of any Anderson film since his low-budget debut, Bottle Rocket. (Note: the word “comparatively” is doing a lot of heavy lifting in the previous sentence; we’re still talking about a Wes Anderson film.) The titular train of the film is the most claustrophobic main location of any Anderson movie—far smaller than Rushmore Academy, the Tenenbaum household, or Steve Zissou’s massive ship—and several scenes of the film take place in the open spaces of India’s landscapes. Darjeeling was also the first Anderson movie filmed and set in another country, so the local culture provides a lot of the visual flare that Anderson typically relied on set decoration for.

This could be a product of where and how The Darjeeling Limited was written. Anderson went to France to co-write the film with Jason Schwartzman and Roman Coppola, both of whom were in the midst of filming Sofia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette at the Palace of Versailles. One must imagine that seeing such opulence every day inspired the attempt to set a film in a slightly more exotic location than a US prep school or NYC brownstone. Writing the film in France also probably inspired the location of Hotel Chevalier, the short-film prequel to The Darjeeling Limited that was released online as an amuse-bouche to the main film (and which probably deserves its own lengthy breakdown and appreciation).

What might have initially seemed a one-off inspiration has proven contagious. Subsequent Anderson films have been set in Hungary and Japan, and he’s made two stop-motion animation films and two period pieces. In fact, though Anderson’s first four films were all live action and set in the American present, none of his five films since have met those criteria. (Yes, all of Anderson’s films always feel like they anachronistically exist a bit outside of time, but he didn’t make a film overtly set in the past until 2012’s Moonrise Kingdom.)

“These emotionally stunted young men all needed to confront their father figures with the shit jobs they did.”

But just as Darjeeling launched Anderson’s willingness to explore new settings and visual ideas, it also marked the end of the dominant themes in his career to that point. Sending his characters—three brothers—on an emotional sabbatical through India took Anderson on the same journey. Like Rushmore, Tenenbaums, and Life Aquatic before it, The Darjeeling Limited is about absent fathers (or father figures). But for the first time, Darjeeling approaches those themes differently. The three previous films were all, in their way, about son confronting father. These emotionally stunted young men all needed to confront their father figures with the shit jobs they did, those fathers needed to see the results of their actions, and a reconciliation or sorts needed to be reached.

But this doesn’t happen in The Darjeeling Limited. There, the absent father is literally absent. The movie takes place one year after his death and, even in the flashback sequence, he is never seen. The movie is never about confronting his absence, but rather is about learning to accept it—an Anderson first. And in a further twist from the established Anderson oeuvre, the brothers here are actually searching for their mother, who didn’t show up to their father’s funeral and has been out of contact, apparently living in a convent in a remote part of India (because of course she is).

This gender swap for the role of the sought-after parent may seem like a simple case of a cosmetic change hiding a same-as-it-ever-was plot device. And that’s kind of true. But this was also a huge leap for Anderson at the time. In his four previous films, women had only occupied two roles: caretaker or object of puppy love. (And in the case of Olivia Williams’ teacher in Rushmore, both.) Anjelica Huston’s role as the estranged mother in The Darjeeling Limited represents the first time a female character in an Anderson film mattered more for her specific substance than for her simple proximity to the male characters that badly needed affection. In fact, her lack of proximity is the principal plot device.

In both the absent father and the mother that refuses to rejoin the clan, The Darjeeling Limited is ultimately about accepting finality, and learning to fight off the helplessness that sometimes involves. In the climactic scene, as the three brothers race to catch their already-on-the-move train, they realize they can’t run as fast as they need to while lumbering with the awkward suitcases they’ve been schlepping around. One of them shouts, “Dad’s bags aren’t gonna make it!” At which point the film, for the third time, switches to a single, slow-motion shot with the characters moving across the screen as a Kinks song drowns out all other sound, and we see the three brothers finally shed their dad’s baggage—which had become their own—and start to move on with their life.

“Like the old saying goes, all unhappy families are unhappy in their own, unique ways.”

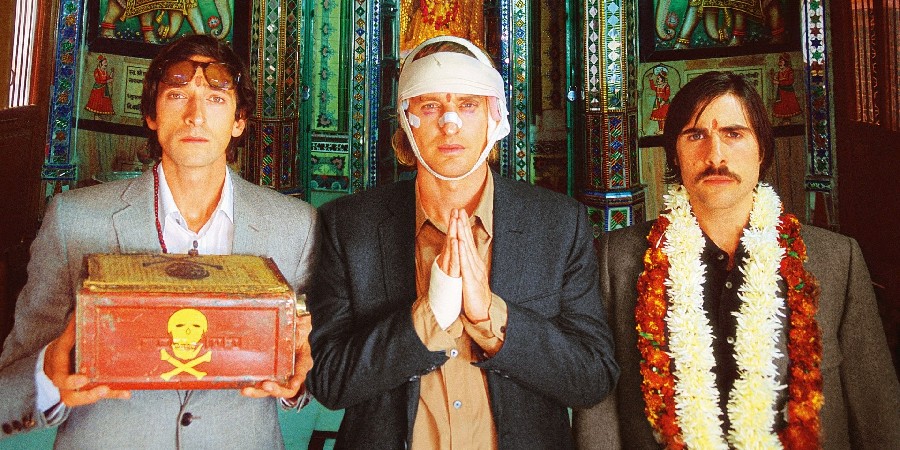

These three shots—the Kinks trio, if you will—form the emotional and stylistic heart of the movie. All three songs are from the Kinks’ 1970 album, Lola Versus Powerman and the Moneygoround, Part One. The first shot, set to “This Time Tomorrow,” is at the beginning of the film, and shows Adrien Brody’s character throwing his bags onto the train as he runs to catch it, beginning our journey. The second shot, set to “Strangers” and at about the midpoint of the film, shows the three brothers walking to attend the funeral of a local village boy they tried and failed to save from a raging river current. And the aforementioned third, at the end of the film, is set to “Powerman.” It’s surely no coincidence that the scene where the characters emphatically regain their emotional autonomy is set to a song called “Powerman.”

That the baggage in the film was all monogrammed with their father’s initials was more than a nice visual detail. Like the old saying goes, all unhappy families are unhappy in their own, unique ways. Baggage from our parents is never generic. All of our baggage is always monogrammed. But the characters weren’t the only ones shedding their baggage in this scene; so was Wes Anderson. After four straight films about young men (and one young woman: shoutout to Margot Tenenbaum) dealing with absent fathers, Anderson hasn’t returned to this theme since. Dad’s baggage didn’t make it onto the journey home, and neither did Wes’s.