In the world of Julia Ducourneau’s Titane, nobody survives a collision intact. Even when characters walk away from various wreckages with their lives, writer-director Ducourneau knows that nothing can ever be the same – transformation is inevitable, and possible only by the piecing back together of the self in the wake of such a crash. The first of Ducourneau’s many collisions is a mundane one, depicted with undramatic sound and apathetic camerawork, signalling very little out of the ordinary.

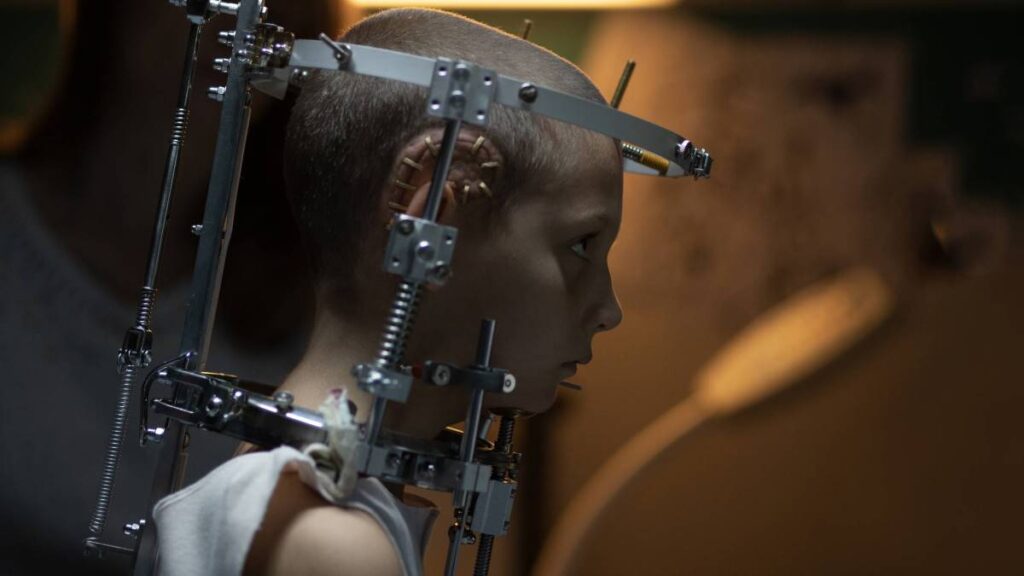

For Titane’s protagonist Alexia, however, her incident (in fact an abusive encounter with her father) is anything but mundane, leaving her with a permanently fractured familial bond, a titanium plate in her head, and a complex adoration for the vehicle that caused her injury. Fast forward several years and Alexia knows nothing but the violence that transformed her. Still fixated on cars, she works as an erotic dancer at car shows under the watchful eye of the male gaze.

In her spare time, she becomes an unstoppable violent force, with almost every human interaction she has hurtling quickly to a bloody end. Whether it’s an overfamiliar fan or a concerned lover is of no distinction – anybody who gets caught in the crossfire is met with violence. Eventually, even Alexia herself becomes a victim of her own violence when, following a murderous rampage she is forced to physically transform, disguising herself as, and eventually becoming, something new: Adrien.

Official Feature and Short Film Line-up Unveiled for the 7th Femme Filmmakers Festival

Alexia assumes the identity of Adrien, a child who went missing a decade prior, and moves in with his father, Vincent, an aging firefighter who is eager to accept that his son has returned, and it is with their relationship that Ducourneau closes in on her philosophy. Each character represents violence or love as a transformative force – Alexia, with her indiscriminate annihilation of anyone that comes too close, is forced to pause against the crushing weight of Vincent’s love for Adrien.

Watching Titane, a gruesome and incessantly violent film, any notion of “the power of love” might seem overly romantic or sentimental, but Julia Ducourneau could never be described as either of those things. Vincent’s love for Adrien matches Alexia’s violence beat-for-beat in its intensity, at once both endearing and pathetic, oppressive and humanising. It is a love that defies reason and reality. It is a love that says things like “If anybody hurts you, I’ll kill them, even if it’s me”. In short, Vincent’s love is unconditional.

Ducourneau’s conception of love is transformative purely because it is relentless; it is a love that crushes all else, leaving no room for something as inconsequential as reality. If Titane is a movie about collision with transformative forces, then perhaps where Ducourneau settles is that such meetings need not always end in mutual destruction, but in mutual reshaping. One thing does not become another, but rather becomes one with it, forever inseparable.

It is also in the contrast between Alexia and Vincent that Titane becomes fluid, diving headfirst into murky waters of gender, familial roles, and complex bodies. When we first meet adult Alexia, she cuts an androgynous figure, donning lipstick and lingerie as dress-up rather than anything real and with her dancing, all overwrought gyrating and naked sexuality, barely resembling dance at all. The superficially feminine traits Alexia adopts are thrown in the audience’s face so blithely in contrast to her violence that they parody the very concept of femininity. There is nothing stereotypical about Alexia, no matter how hard you look.

‘Titane’, ‘A Hero’, ‘Annette’ among Festival de Cannes Winners 74th Edition

Vincent, on the other hand, is nurturing, fond of dancing, and fixated on his body. Ducourneau begins quite simply, making femininity the weapon and masculinity a protective presence. What complicates such a simple inversion is Alexia’s complicated pregnancy. Alexia is a machine in flux, her skin and body constantly permeated against her will; Ducourneau’s camera prods at the reality of a constantly changing female body, and it is here that she finds horror, by transplanting it onto a newly masculine form.

Ducourneau complicates matters further by blending her already messy gender roles with the nuclear family, linking masculinity and motherhood, fatherhood and femininity, and even playing with the taboo implication of a potentially perverse heterosexual dynamic sexuality between Vincent and Alexia. In Titane, preconceptions of biology, bodies, and social convention do not matter all that much – what matters is Ducourneau’s twin transformative forces of violence and love, and how they shape individual realities.

Alexia’s history of violent trauma turns cars into sexual beings, just as Vincent’s persistent love for a vanished son leads him to merely hand Alexia a towel when he sees her naked, pregnant body, consciously choosing the truth they both wish to adhere to. It’s a tender moment, and one that exemplifies both the pair’s dynamic and the film’s attitude to gender perfectly – that when a force of such magnitude has you in its sights, gender is there only to be flung aside, and to make way for whatever is shaped in its absence.

‘Titane’, ‘Mass’, ‘The Power of the Dog’ Winners at the 3rd Annual Pandora International Film Critics Awards

In her novel Geek Love, another text about society’s outsiders and the complicated love they have for each other, author Katharine Dunn writes “I have wallowed in grief for the lonesome, deliberate seep of my love into the air… In the end I would always pull up to a sense of glory, that loving is the strong side. It’s feeble to be an object. What’s the point of being loved in return, I’d ask myself. To warm my spine in the dark?”. Titane is filled with those who love, often unrequitedly, and the objects of their affection.

The most obvious example is Vincent and Alexia/Adrien as the film’s core dynamic, but Alexia is equally as objectified by her audience as a dancer. If we widen the parameters to include fascination with literal, physical objects, then Alexia’s fixation on Justine’s nipple piercing, her sexual relationship with a car, and her childhood affection for the car that hurt her are all valid examples of this dynamic. When Alexia becomes an object of love herself, it is a startling transition in which she is somewhat disempowered, made vulnerable by being shown tenderness.

Throughout Titane, Alexia is shown only conditional love – the love of her parents and the first car are both contingent on forgiveness of the harm they caused her, and as an adult, she is shown parasocial love on the condition of upholding a specific, overtly sexualised femininity. Those relationships create a woman who responds to love and intimacy with violence, and to violence with intimacy and love. In Titane, to love rather than be loved is perhaps (as Dunn would say), the stronger side, but to be an object of love is not feeble. It is to be rendered human.

FemmeFilmFest7 Review: J’ai Le Cafard // Bint Werdan (Maysaa Almumin)

When Alexia’s child is eventually born with a spine made of titanium, it is a perfect final synthesis of Ducourneau’s themes of body horror and radical acceptance. Surgical traits cannot be inherited – our scars are our own to carry – and yet somehow, Alexia’s bizarre half-human, half-metallic child does so. Metal, the symbol of Alexia’s traumatic, violent past, is no longer an intrusion on her body, but instead something that can make the body of her child stronger, more resilient.

To a pessimist, there is probably much to be mined in this imagery about cycles of violence and inherited traumas, but as an optimist, the image strikes me as reminiscent of Dunn’s question about the function of requited love – “to warm my spine in the dark?”. Titanium is a material that does not bow easily to anything, including heat, and is in fact one of the few metals that can actually be strengthened by exposure to it. In Ducourneau’s Titane, this is exactly the transformative and unsentimental power of love – to find us in the dark and make stronger the spines our mothers have forged for us.