Some artists are ignored, while others are simply unlucky: Martha Cooper was both. Her photographs captured artists at work, documenting process as well as final products.

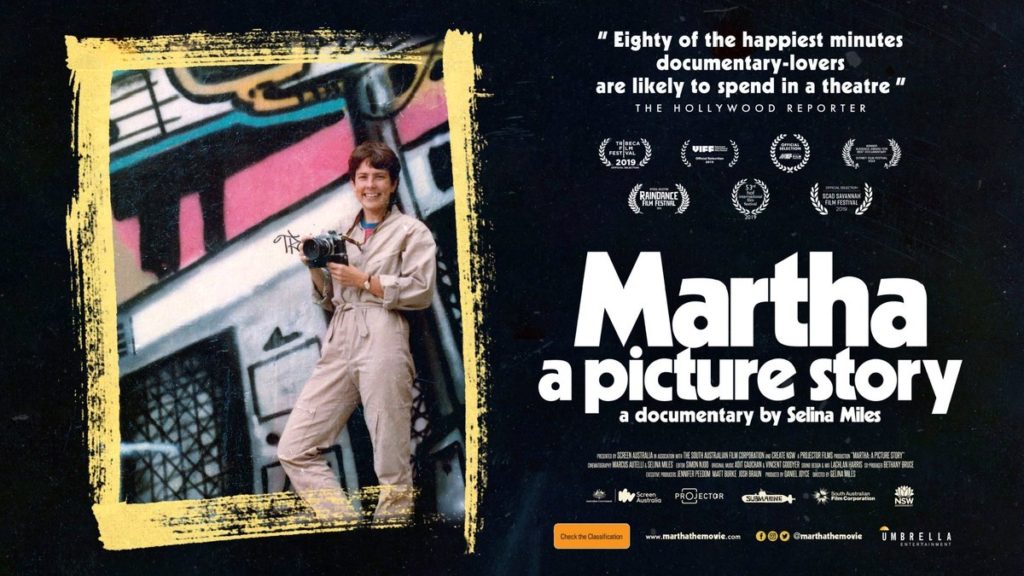

Unfortunately for her, many of those photographs were of graffiti artists in the 70s, a time when street art was reviled by the government, and her photos rarely saw the light of day. In her excellent documentary, director Selina Miles explores the stubborn honesty Cooper brought to her work, and America’s changing perceptions of street-art. It’s a fascinating life story, but the best reason I can give to watch Martha: A Picture Story, is that it asks how someone so ahead of her time can remain an outsider.

In 2018, Cooper sits in a meeting with a gallery curator, reviewing her recent Baltimore street photography. The curator throws out photos of cute children and smiling faces, claiming that people want “serious” art. Cooper is surprised, but doesn’t fight back; time and time again we’re told she is no legend in the photography community, at least not in a way that pays the rent. She needs to sell photos, and to do that she needs this meeting to go well.

Documentary Review: The Great Hack

There’s no argument between Cooper and the curator, just a series of pained glances and half-finished platitudes about “audience taste.” At the end of the conversation, the curator justifies his pickiness with another platitude: “New York is sort of the capital of the world.” Martha responds, “At least that’s what New Yorkers think.” Cooper is the rare photographer, famous for her New York period, who isn’t obsessed with New York City. That’s not an automatic badge of honor, but it is a rare thing to find an artist as unbothered by the movement they inspired. And who am I kidding, it’s also an automatic badge of honor.

Miles spends the first 20 minutes bringing viewers to speed. Cooper’s National Geographic internship and assignments with the New York Post are only discussed briefly, but they’re not sugar-coated. In the 70s, Cooper wanted nothing more than to work for National Geographic; when the opportunity came, it was only for a six-month stint. On to the next dream, or more accurate to Cooper, the next job. She lasted longer at the Post, but at the cost of assignments like “look for cleavage” at Olympic training sessions. Miles makes time for anecdotes like these, moments that make you feel you’ve lived alongside Cooper in the best, and darkest, times of her career. For the film’s ending, she goes so far as to create a new one…

Drawn to the risk, Cooper travels to Berlin to shoot “1UP,” a street-art collective that invites her to photograph their latest (illegal) subway art. It’s a novel ending, though there isn’t much time to get to know the artists. When covering her graffiti and street-life periods, there are numerous interviews with the people Cooper photographed, giving them a brief, but effective chance to place Cooper’s work in context with their lives; it’s one of the main reasons the film is so consistently entertaining, because the filmmakers seem to care as much about the people in the photos as they do the artist.

Documentary Review: Knock Down the House

There’s a frenetic “running through the subways” sequence (a shock of tension that places a welcome urgency on Cooper’s present work), then she’s back in America, being told there could be consequences for publishing the photos. More than an understanding of the artists, this communicates that Cooper’s desire to create is what pushes her. Not trends or money, but the risk of failure, the excitement of a new artist’s style. Effectively, it places Martha back at the center of the film, without deifying her as the reason the artists she captures become famous. They’re taking the risk, and she’s just the photographer (but a damn good one).

Like Cat Stevens singing “I let my music take me where my heart wants to go,” Cooper’s photos are a vessel for her, more than anything else. Rejected by popular art, Cooper follows what draws her, and in the dramatic, energetic ending, she finds it in the forbidden nature of graffiti. It’s a bit silly to throw oneself into a dangerous situation to relive young thrills, but in the chaos and aftermath of Berlin, it’s clear that Cooper’s focus isn’t in her glory days, but in documenting the processes and creations of artists that are interesting to her.