Recalling, and unable to shake off, the tragic events in Alton, Texas in 1989, when 21 children died in a bus accident, Russell Banks wrote the novel, The Sweet Hereafter. In this case, moving events to upstate New York in Sam Dent. Banks’ well-regarded book told the story of a community ravaged with heartache, following the school bus rearing off road into an embankment, killing all but two.

On the back of his success with the excellent Exotica in 1994, Canadian filmmaker Atom Egoyan was booked to make a movie in Hollywood. When he was handed a copy of The Sweet Hereafter by his wife, he was naturally conflicted. Drop a huge American thriller on the instinct of a novel’s resonance? Assigned jury duty at the 1996 Cannes Film Festival, Egoyan only needed a few days out of the mainstream bubble to make his decision.

“Egoyan’s screenplay is extraordinarily grounded. Rich in character and dialogue.”

The sacrifice, and the embrace of a great story, paid off. A year after his venture to the French Riviera, Egoyan’s flawless adaptation of The Sweet Hereafter would take three prizes at Cannes in 1997 – including the Grand Prix. The film was a critical hit, later bagging the filmmaker two nominations at the Academy Awards, for Best Director, and Best Adapted Screenplay.

The Sweet Hereafter‘s praise begins with the writing. Egoyan’s screenplay is extraordinarily grounded. Rich in character and dialogue, as well as seamlessly assembled through staggered points of view. The accompanying, but never intrusive, narration comes from 15 year-old Nicole (Sarah Polley). In large part, reading from The Pied Piper of Hamelin, an ingenious addition by Egoyan, as the classic tale juxtaposes The Sweet Hereafter‘s prominent themes.

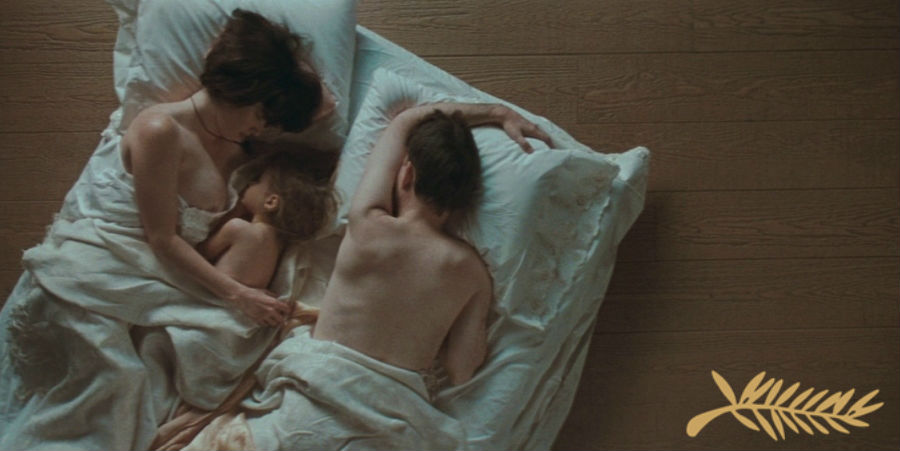

While babysitting, Nicole reads the story to the two children of Billy Ansel (Bruce Greenwood), the night before the film’s central, tragic event. Recently widowed Billy, meanwhile, is away sleeping with Risa, a neighbour’s husband.

The Sweet Hereafter circles around the small town’s people, and the lawyer (a masterfully subdued Ian Holm) looking to file a negligence suit, as well as drifting between two significant timelines. The day before the ill-fated school bus accident, and the social aftermath, as parents grieve and a community steadily crumbles.

“Ian Holm’s under-stated portrayal of such a complex man is superb.”

In Russell Banks’ book, the lawyer, Mitchell Stephens could be described as a slick, ambitious man. But in Egoyan’s film, the main drive has a whiff of desperation from personal experience. Ian Holm’s under-stated portrayal of such a complex man is superb. Every nuance of a man cautiously ruthless in pursuing these broken parents, while easily distracted by his own worries, is poignantly realised by the late British actor.

Mitchell gets Risa and Wendell, who lost their son, on board without a struggle. And then utilises an empathetic approach to have Wanda and Hartley Otto warm to the lawyer, following the death of their adopted boy. The two survivors of the incident, Nicole, and the driver of the bus, Dolores Driscoll (Gabrielle Rose), would be implicitly key witnesses.

Dolores, who suffered a neck injury, has lost her chirpy nature, and is now brimming with remorse. She also takes care of her husband, Abbott, who is recovering from a stroke. When Dolores asks Mitchell to call her by her first name, he is brought into a more familiar place, parting slightly with his initial cold professionalism. With photographs of the school children on her wall, when they refer to Bear Otto, Dolores says “He would have made a wonderful man”. The fact that he won’t, is an all-too painful truth.

Nicole’s parents, Sam (Tom McCamus) and Mary, agree to co-operate with Mitchell’s investigation. When we open on Nicole, she is singing outdoors, her father watches proudly. That nervous energy between them makes sense later. Nicole reading the story accompanies a scene where she and her father head to a barn. The intimacy between them leaves nothing to the imagination.

“With the kids screaming far off, and Billy’s unfathomable expression, its a horrific moment.”

Billy, the most reluctant to go down the negligence path, and hostile to Mitchell, is far more closed off. He saw the accident happen. He would usually drive behind the bus on his way to work, and wave at his kids through the window.

The suddenly stunned reaction of Billy, as he drives, is startling. He clearly watched the bus career off the road. We see the bus slide far off onto the frozen river, which cracks under the weight, and the bus starts to sink. With the kids screaming far off, and Billy’s unfathomable expression, its a horrific moment. Nobody should ever have to see anything like that.

The cause of the accident is a huge chunk of Mitchell’s motivation. Is it down to the transport authorities? Was it simply the ice? The weak guardrails? Maybe Dolores was driving too fast? Terribly bad luck?

Whatever caused the accident, Nicole’s deposition in one of the film’s many memorable segments, rattles the whole agenda. Now in a wheelchair, Nicole goes from not remembering the incident, to have it apparently come back to her. The final scene, has Nicole finishing the Pied Piper story the night before the tragedy – when she could walk, and the two children were alive.

“Life is precarious at the best of times, The Sweet Hereafter shows us this with a melancholic breeze.”

What Atom Egoyan does so remarkably well with The Sweet Hereafter, is disrupt the serenity of a Canadian mountain town (exquisitely captured by cinematographer Paul Sarossy). But with such a delicate downward slide. Grief of children is horrendous on its own, but the deep-layered baggage of the locals is more fragile than ever. Life is precarious at the best of times, The Sweet Hereafter shows us this with a melancholic breeze.

And in that vein, Mychael Danna’s score gently showers the film with such a wistful, balanced tone. There’s a true sense of loss as well as hope in the composition. Music which flows like the cold, snowy outdoors of the film’s location. The sound design, too, reflects the acoustics of a troubled commonwealth. When Mitchell arrives, and looks at the battered bus, we hear the distant sound of young children screaming (as Billy experiences). It seeps under the surface of your skin, there’s the aura of woe dispersing into this ordinary world.

Mitchell, himself, is no stranger to personal strain. An early phone call with Zoe, his daughter, reveals a wounded bond, teetering on severed ties. Her drug addiction has caused hefty damage, and when he gets stuck in a car wash, what might have been a comic moment, for him it exasperates his agitation.

As a lawyer, he approaches the compensation claim like a cherry-picking exercise for the locals. The most sensitive and sympathetic in the judge’s eyes yields a better chance. It does not take long for him to show some empathy and emotion – not to say he didn’t have it before. As a businessman, he tells them that he is clearly here to represent their anger, not their grief. Mitchell does give the impression that his aggression is personal. In particular, when he refers to the prevention of such hazards to children.

“Atom Egoyan is completely tuned into the psyche of every character.”

When Mitchell thinks of his daughter, he drifts off. On the plane to see her (in a timeline way beyond the bus accident), he is seated next to Allison, an old friend of Zoe’s. Their re-acquaintance is halted in mood by her asking how his daughter has been.

Mitchell remembers the summer he almost lost her. She was just three years-old, and he was woken by Zoe’s wavered breathing. It seems there was a nest of baby black widow spiders where she slept. A young Mitchell (who we never fully see) was advised by the emergency service to hold her on his lap, and be prepared to make a cut in her windpipe so she could breath, if they were not to make it to the hospital in time.

Mitchell is extremely emotional telling the tale. And understandably so. The shot of the toddler looking toward us with a kind of fixated uncertainty, Mitchell’s hand clasping an unfolded shaving razor, is astonishing. The hold on the child’s face encapsulates both the preciousness and the anguish of such an ordeal. An unforgettable image.

Atom Egoyan is completely tuned into the psyche of every character. Their sadness, their hopes, their conflicting emotions. Mitchell, Nicole, Billy, Dolores, everyone in The Sweet Hereafter – they all carry the burden of personal suffering, each in their own way, given their place in the world.

When Zoe gives Mitchell some horrible news, we cut briefly to the image of the three year-old again. They tell each other they can hear their breathing. Somehow reunited in the distance through the mutual fear they face. And you just about feel it yourself.