The road to Halloween is paved with good films. Wherein we countdown to the spirited season with a hundred doses of horror. 25 days to go.

Ingmar Bergman’s Hour of the Wolf is an interesting film from its first seconds. A title card tells us that the film is ‘real’, based on a diary given to Bergman. This sense of reality is instantly subverted. Under the credits, we hear the crew setting up, calling, ‘Quiet. Ready for a take.’

Then we see Alma (Liv Ullmann) as she wanders over to the camera. It’s movement, as it follows her, sticks out, a continued remind of the artifice inherent to film. She talks directly into the camera, it should feel confrontational as Ullmann masterfully shows the horror bubbling under Alma’s emotionless front. But instead, it feels detached. Distant.

Read More on Ingmar Bergman’s Films: Shame (1968)

This distance is invoked again as Johan (Max von Sydow), the famous artist and husband of Alma, in another pained, sleepless night, shows Alma how he feels by timing a minute. Waiting in silence for it to pass. We feel every awful second of it, of our time dragging along.

Even though the closing ‘interview’ feels a little close to the end of Psycho, Bergman carefully carries us back into the films reality, washing the memories of that distance away as we slowly, rhythmically see Alma and Johan moving to this island, almost without a word. We drift gently with it.

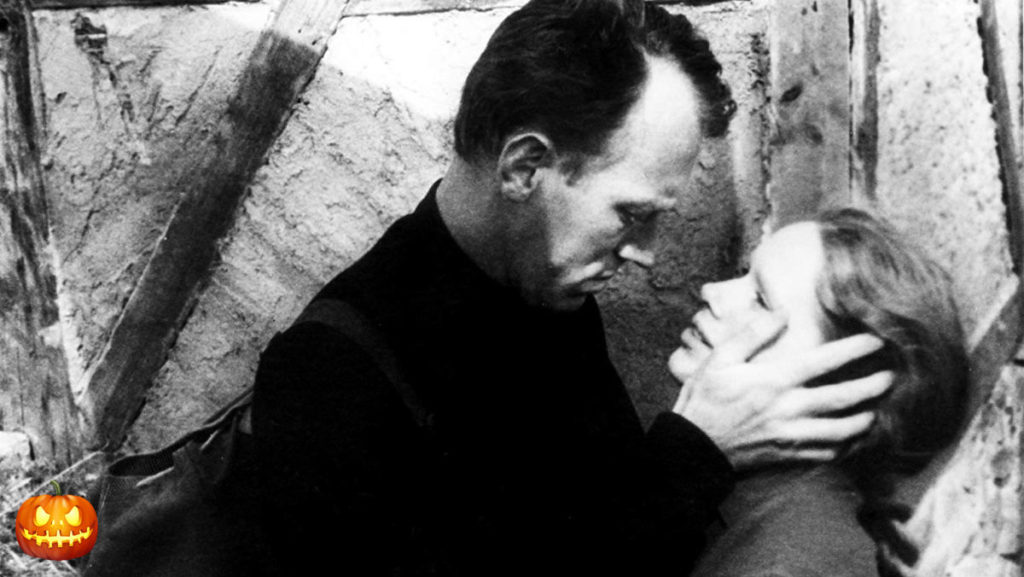

Despite moving to somewhere as isolated as an Island, Johan and Alma’s relationship is far from solid. When they embrace, Johan’s face stays blank, laundry blowing over him. He is replaced, or revealed by its whiteness. He is not there. Later, when he tries to embrace her, Alma pushes him away, wailing. But as he turns away, leaving, she only cries harder. The two seldom talk, mostly one monologues whilst the other sits in silence, hardly reacting.

Read More on Ingmar Bergman’s Films: The Virgin Spring (1960)

Much of this conflict is born of the relationship between artist and ‘muse’. Early on, when Alma tries to embrace Johan, he subtly pushes her away with his canvas. He also makes her pose for him, in front of the dramatic tree outside their house. In that moment there is little difference between the tree and her. When Johan’s nightmare creations become flesh, one poses with that very same tree.

There some hints, speculations of Alma’s power of him. Johan is a fragile, broken person. Now of his creations tells Alma not to burn the drawings they came from, that haunt Johan. She can keep these dark thoughts alive. But in the end, she doesn’t even get to be his muse. His Ex, Veronica does. She’s turned to a symbol in his world, as he revives her dead, naked born, through only a touch.

As these ‘man-eaters’, these nightmare creations, consume Johan more and more, Alma too is consumed. Into him. ‘Man and Woman shall be one of flesh’, Johan’s visions bleed into Alma’s world. During the interviews that bookend the film, Alma is much different from the wide eyed ingenue we see throughout the film. She is quieter, stiffer, less expressive. She even dressed differently. Wearing the dark, heavy clothes he did. Once in contrast to her pure whites.

Read More on Ingmar Bergman’s Films: Summer With Monika (1953)

She shares his anxieties. The camera’s point of view clearly shifts during an uncomfortable dinner in the house of the Island’s owner. People walk right up to the camera, invading its space, a camera that can’t hold a frame, moving quickly from one close up to the next, sometimes not being in focus for one or both, with jump cuts breaking into the middle of a moment. But later, Johan seems to shoot Alma, callously, coldly. She is part of him, but he is not a part of her.

But as all consuming and aggressive as Johan is, it’s born more from his inability to control, than a desire to. Even his artistic impulses, the centre of his life, are not his own. He was ‘chosen’, like a ‘five-legged calf’ or a ‘monster’, he describes. It is some kind of curse, a weight he has no choice but to carry. A possession, a kind of consumption. Von Sydow’s physical resemblance to Bergman seems more important here than ever.

As the interior and exterior worlds bleed together, the owners of the Island transformed into the man-eaters, the castle becoming a reflection of Johan’s mind, the world of art and reality are also bleeding. Bergman can only expose himself, he must create this art, he is compelled to, possessed. But he also must live of it. Johan hides his art from a neighbour who tries to talk to him, but Bergman lets us all see his scars.

Read More on Ingmar Bergman’s Films: Through a Glass Darkly (1961)

Johan tells Alma a story of his childhood, one Bergman has told variations on, of being locked in the closet, of seeing monsters, of begging for forgiveness to the parents who put them there. When Johan’s father asks how many strikes of the cane he deserves, they reply, ‘as many as possible.’ Bergman exposes himself not just because he has to, but because he feels he deserves it, ‘In this house, we are used to humiliation’ one of the apparitions says.

Underneath it all, is a helpless search for connection. No matter how close Alma and Johan were, even as they seemed to become one, there was always some unbearable distance they couldn’t cross. No matter how close, they could not touch.